The short answer that this folk song describes an actual event that took place on February 8 and 9, 1889. That being said, there’s an almost endless array of discussion/argument about its wording. To give you just a taste of this backing and forthing, there are whole threads on discussion forums talking about why the song says “from Yarmouth down to Scarborough” when Scarborough is clearly north of Yarmouth. (Don’t believe me? Here’s the link to Google maps.) Since I’m no sailor, I can’t pretend to understand the reasoning as to why this wording is perfectly accurate in nautical terms, but it has something to do with the direction of the winds and currents. I think. And that’s just one small point in the whole mix. If you’re of a mind to do some reading yourself, google “Grimsby Town fishing disaster” and you’ll have more than enough to keep you busy. (Don’t just google “Grimsby Town” on its own, as all you’ll get is stuff about their football club—soccer to us ignorant Americans. Very interesting in its way, of course, but not much to our point here.)

People from Grimsby are officially called “Grimbarians,” but their unofficial nickname is “codheads,” a reference to the town’s fishing history and now usually applied (unflatteringly) to their football fans. But Grimsby (along with the entire North Atlantic coast of the UK) no longer has much of a cod industry, as they lost out to Iceland in a series of confrontations, disputes and judgments known collectively as the “Cod Wars.” (I got rather tickled that Wikipedia has the statement “not to be confused with the Cold War.”) At the time the lyrics to our song were written, however, Grimsby was very much in the cod business, and individual losses of boats and lives were all too common. This specific disaster, however, stood out for the large number of boats and men lost at one time, possibly the result of a freak tidal wave.

The first officially published version of the lyrics doesn’t appear until 1986, and this source explains how the original version came to be written:

“‘In Memoriam of the poor fishermen who lost their lives in the Dreadful Gale from Grimsby & Hull, Feb. 8&9, 1889’ is the title of a broadside produced by a Grimsby fisherman, WIlliam Deld, to raise funds for the bereaved families. It lists 8 lost vessels, the last 2 from Hull: Eton, John Wintringham, Sea Searcher, Sir Fred, Brittish Workmann, Kitten, Harold, Adventure & Olive Branch. I addition the names of some of the lost sailors are given, & there is a poem in 8 stanzas. This past into oral tradition, & in so doing lost 6 verses & aquired a new one (the last, in which an error of date occurs), together with a chorus & a tune. The oral version was noted from a master mariner, Mr. J. Pearson of Filey, in 1957, and has subsequently, with some further small veriations, become well known in folk-song clubs.” (from The Oxford Book of Sea Songs by Roy Palmer p.274-275, pub. 1986).

The very interesting and actually kind of funny thing is, there are reams of posts about the proper wording of the lyrics when the original broadside is on display in a museum (I think in the Bodleian at Oxford; I didn’t make a note at the time and now can’t find the link). But, as noted above, the original wasn’t written as a song but as a poem to be printed and sold with the proceeds going to help the families of the lost sailors. The chorus was added later, and it seems to have a fair number of variations also. As one post said, “If the words don’t make sense, change them!” So this song has kind of reversed the sequence of events that usually takes place with folk music, with the song normally being composed (if that’s the word) orally, going through a process of change, and then eventually being written down with its variations. Here, we start out with a known written source that then breaks into many different versions.

An article about the disaster from a local newspaper of the time gives a good idea of the disaster’s scope:

Mar 2nd 1889 The full results of the fearful gale of the 9th ult upon the GRIMSBY Fishing Fleet are now becoming known. Of the safety of seven of the missing smacks all hope as been abandoned These vessels are, BRITISH WORKMAN, ETON, SIR FREDRICK, ROBERT’S KITTEN, SEA SEARCHER, JOHN WINTRINGHAM and HAROLD. The total number of lives lost could reach between 70 and 80. This calamity in a single port is one of the most appaling on record.

(The above information about the song and both quotes are from a great resource for anyone who wants to track down meanings and variations of song lyrics, The Mudcat Cafe. A “mudcat” is a catfish, but what such a creature has to do with music, I have no idea. Their logo is a catfish playing a fiddle.)

One more explanation here, and that’s of the line “Many hundreds more were drowned.” This line is from the chorus, which, as noted above, was added later and therefore not part of the original, firsthand description in the poem. There seems to be agreement that this line is just an exaggeration for effect, as a loss of life on that scale would have made the national newspapers. There was probably an assumption that other boats in addition to the ones from Grimsby must have been caught up in the storm, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. The disaster seems to have been quite localized. This particular event seems to have been preserved more by the happenstance of the poem’s distribution than by any uniqueness, though. Every time a wife said good-bye to her husband, a sweetheart to her lover, a mother to her son, or a sister to her brother, she knew there was a good chance that it would be a final farewell. We can enjoy singing the song without forgetting the tragedy that produced it.

Here’s a great recording, with an alternate title “Threescore and Ten”–yet another reference to the inflated number of fatalities in the re-tellings.

I wasn’t able to find any YouTube performances of actual choirs. Here at least are the lyrics, at least in one version:

And it’s three score and ten boys and men, we’re lost from Grimsby town

From Yarmouth down to Scarborough many hundreds more were drowned

Our herring craft, our trawlers, our fishing smacks as well

They long to fight the bitter night and battle with the swell

Me thinks I see a host of craft and they spreading their sails alee

As down the harbor they do glide all bound for the northern sea

Me thinks I see on each small craft a crew with hearts so brave

Going out to earn their daily bread upon the restless waves

Me thinks I see them yet again as the leave this land behind

Casting their nets into the sea, the herring shoals to find

Me thinks I see them yet again and they all on board alright

With their nets close reefed and their decks cleaned up and their side lights burning bright

October’s night brought such a sight, ’twas never seen before

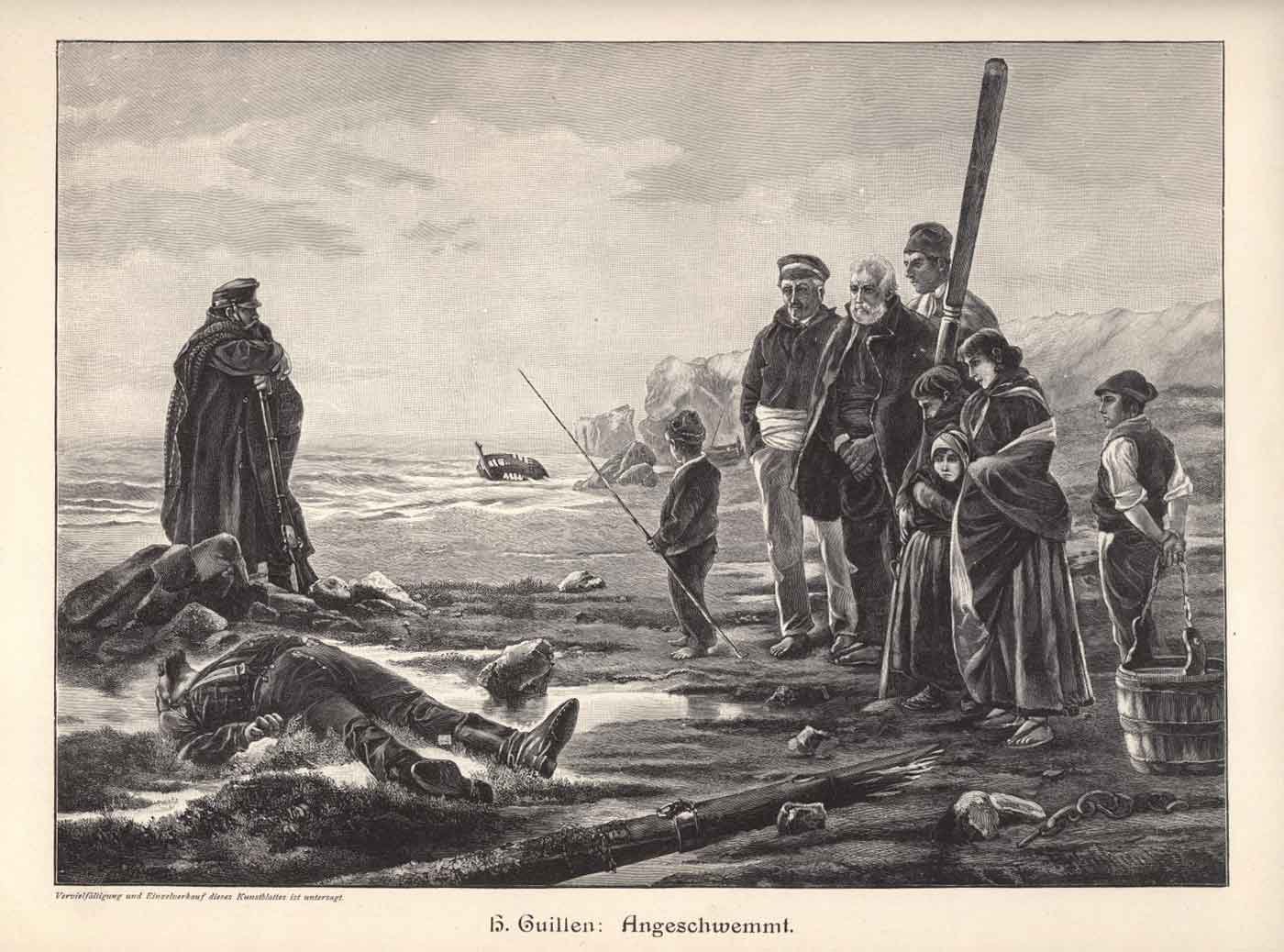

There was masts and yards and broken spars come washed up on the shore

There was many a heart of sorrow, there was many a heart so brave

There was many a fine and hearty lad to find the watery grave.

© Debi Simons